Yellowpaper

(Please, be aware that, whereas this yellowpaper already gives an idea of why a new form of money is needed, still is a work in progress)

Abstract

Money is probably one of the oldest institutions, it is as old as mankind itself. Money was invented before written history began. Consequently, any story of how money first developed is mostly based on conjecture and logical inference. During the last centuries, different money configurations have been proposed, and tested, and many authors have discussed, and exposed, their theories on how money should look like. However, we have not yet found an optimal configuration and all the existing models fail, for one reason or another. The advent of digital money enable us, for the first time ever, to design money that follows the lessons learnt and good practices. Many money configurations are being proposed at a rate not seen before. Unfortunately, for different reasons, most of these configurations, fall short on considering the different aspects and lessons learnt over the centuries and lead to repeat the same mistakes. As a consequence, there is not a real adoption in the mainstream and the different initiatives looks mislead on their goal. This document aims to open a discussion on proposing a comprehensive framework to define the features that should be included in a currency. All of them have been extensively documented in the past but, so far, there is not an unified theory and we think a Quality Theory of Money is long overdue.

Keywords

representative money, cryptocurrencies, cryptocommodities, stablecoins, price formation, stabilization mechanism, tokenomics, private currencies, currency competition, cantillon effects, monetary theory, quality theory of money

1. A Primer in Monetary Theory

1.1 What is economics

generating, moving and distributing value

positive vs normatve economics

1.1.1 What is Value

3 notions of value

1.1.2 Operations with Value

-

generate

-

count

-

persist (short, medium, long term)

-

transfer (decentralization)

-

exchange

-

consume

1.1.3 How is value used?

-

production

-

purchasing power

1.1.4 What is NOT economics

economics is not decentralization, is required but not sufficient

1.2 What is Real Economics?

1.3 What is Money

money wraps value to deliver functions

1.4 What is Financial Economics?

1.5 What is Monetary Theory?

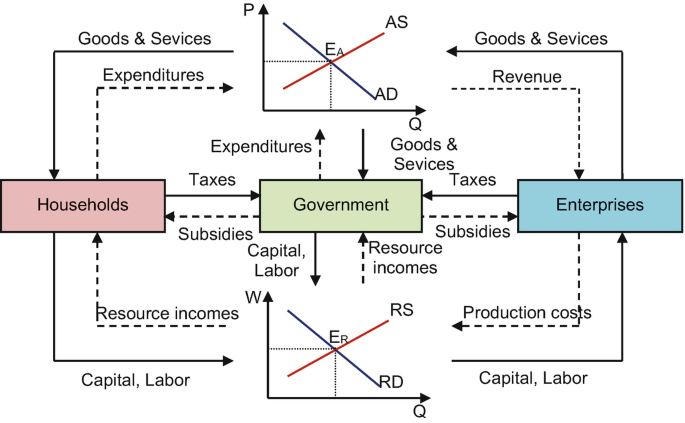

How real economy and Financial System interacts?

| ||

Goods and Services Markets

| Financial Markets

| |

| Real Economy | Money Configuration | Financial Economy |

1.6 Topics Discussed

- Theory of Value

- Money Issuer

- Functions of Money

- Neutrality of Money

- Money Supply

- Fractional Reserve

- Price Formation

- Availability of Credit

- Rate of Interest

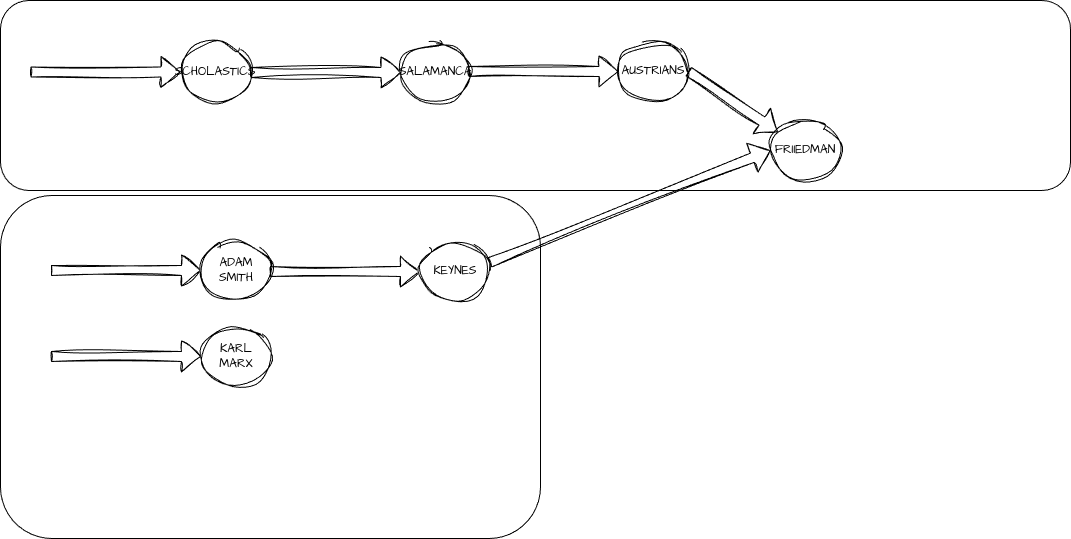

1.7 A Review of Schools of Economics

| School | Authors / Ideas |

|---|---|

| Scholastics / School of Salamanca 1100s-1600s | Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) / Francisco de Vitoria (1483–1546), Martín de Azpilcueta (1492–1586), Juan de Mariana (1536–1624) |

| Subjective value, sound money | |

| Mercantilism 1500s-1700s | Thomas Mun (1571-1641), Jean Bodin (1529—1596), Charles Davenant (1656 – 1714) |

| Objective value, money non-neutral but supported currency manipulation | |

| British Empiricism 1690-1770s | John Locke (1632-1704), David Hume (1711—1776) |

| Subjective value, sound money | |

| Physiocracy 1759-1775 | Richard Cantillon (1680–1734), François Quesnay (1694–1774), Tha Marquis da Mirabeau (1715–1789), Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) |

| Objective value (land), sound money | |

| Classical 1770s-1870s | Adam Smith (1723-1790), Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834), Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832), David Ricardo (1772–1823), John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) |

| Objective value, Long-run money neutral, sound money | |

| Marxist 1867–present | Karl Marx (1818 - 1883), Friedrich Engels (1820-1895), Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) |

| Objective value, money no neutral, sound money | |

| Neoclassical 1870s–present | Alfred Marshall (1842-1924), Léon Walras (1834-1910), William Stanley Jevons (1835–1882), Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), Knut Wicksell (1851–1926), Irving Fisher (1867–1947) |

| Subjective value, money neutral, fractional reserve | |

| Austrian School 1871–1980s | Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850), Carl Menger (1840-1921), Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851–1914), Friedrich Von Wieser (1851-1926), Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973), Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883-1950), Henry Hazlitt (1894–1993), Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992), Murray N. Rothbard (1926-1995) |

| Subjective value, money no neutral, sound money / currency competition | |

| Keynesian 1936–present | John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), Paul Samuelson (1915–2009) |

| Subjective value, money only neutral on full employment, fiat money | |

| Monetarism 1950s–1980s | Milton Friedman (1912-2007), George Stigler (1911 –1991), Gary Becker (1930-2014) |

| No theory of value, long-run neutrality of money, fiat money with fixed growth | |

| Post-Keynesian 1970s-present | Hyman Minsky (1919–1996), Michal Kalecki (1899–1970) |

| Subjective value, money not neutral, fiat money | |

| New Keynesian 1970s-present | Joseph Stiglitz (1943), Ben Bernanke (1953) |

| Subjective value, money not neutral, fiat money | |

| New Austrian School 1980s–present | Israel Kirzner (1930), Antal E. Fekete (1932), Hans-Hermann Hoppe (1949), Joseph T. Salerno (1950), Lawrence H. White (1954), Huerta de Soto (1956), George A. Selgin (1957), Steven Horwitz (1964-2021) |

| Subjective value, money no neutral, sound money / currency competition | |

| Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) 1990s-present | L. Randall Wray (1953), Stephanie Kelton (1969) |

| Subjective value, money not neutral, fiat money with government intervention |

1.8 Economic Eras

| Dominant School | Main Ideas |

|---|---|

| School of Salamanca 1492-1539 | |

| Mercantilism 1539-1776 | |

| Classical 1776-1870 | |

| Neoclassical 1870-1933 | |

| Keynesianism 1933-now |

MODELING MONETARY THEORY

Understand how different monetary configurations are created, how they perform and how they deliver the attached value

2. The Extended Theory of Value

2.1 Notions of Value

2.2 Commodity Value

From its origins in medieval times, the historical evolution of the value debate became locked into a centuries old dialectical conflict between the objective and subjective approaches. This study has traced the waves of value theories which oscillated back and forth towards each approach, until Walras and Marshall accommodated both rivaling approaches of value within their separate General and Partial Equilibrium frameworks.

2.2.1 Intrinsic Value

Intrinsic value theories started as early as 1600s; natural value by W. Petty (1623-1687); value based on land and labor, R. Cantillon (1680-1734); value and market price, N. Barbon (1640-1698); objective value, intrinsic value, A. Smith (1723-1790); value driven by labor, K. Marx (1818-1883) and D. Ricardo (1772-1823).

An intrinsic theory of value (also called theory of objective value) is any theory of value which holds that the value of an object or a good or service is intrinsic, meaning that it has in itself and can be estimated using objective measures. The theories of the classical school of economics look to the process of producing an item, and the costs involved in that process, as a measure of the item's intrinsic value.

2.2.2 Marginal Revolution

Marginalism as a formal theory can be attributed to the work of three economists, W. Jevons (1835-1882) in England, C. Menger (1840-1921) in Austria, and Walras in Switzerland. William Stanley Jevons first proposed the theory in articles in 1863 and 1871. Carl Menger presented the theory in 1871. Menger explained why individuals use marginal utility to decide amongst trade-offs. Léon Walras introduced the theory in Éléments d'économie politique pure published in 1874. Walras was able to articulate the utility maximization of the consumer far better than Jevons and Menger by assuming that utility was linked to the consumption of each good. Marginal utility focused on the value that the consumer received from the good when determining its value.

Although the Marginal Revolution flowed from the work of Jevons, Menger and Walras, their work might have failed to enter the mainstream were it not for a second generation of economists. In England, the second generation were exemplified by Philip Wicksteed, by William Smart, and by Alfred Marshall; in Austria by Eugen Böhm von Bawerk and by Friedrich von Wieser; in Switzerland by Vilfredo Pareto; and in America by Herbert Joseph Davenport and by Frank A. Fetter.

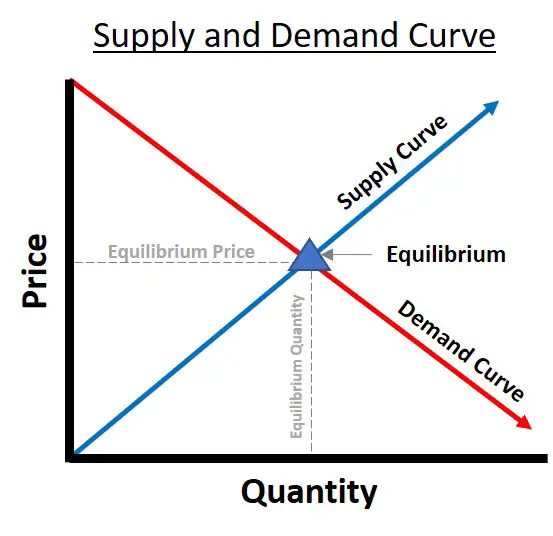

2.2.3 Value as Supply and Demand

Alfred Marshall (1842-1924) (Daraban, 2016) amalgamated the best of classical analysis with the new tools of the marginalists in order to explain value in terms of supply and demand. He acknowledged that the study of any economic concept, like value, is hindered by the interrelativeness of the economy and varying time effects. As a result, Marshall used a partial equilibrium framework, in which most variables are kept constant, in order to develop his analysis on the theory of value.

2.2.4 Capturing Value

Depends on Monetary Standard

Depends on Market Scope

2.3 Fiat Value

2.4 Utility Value

2.5 Non Fungible Backing

2.6 Heterogeneous Backing

2.7 Value Stability

| Short Term | Medium Term | Long Term | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commodities | |||

| Fiat | |||

| Utility / Mathematical |

These are core arguments, will be written at the end when the document gets ready and can be referred as a whole.

3. The Monetary Architecture

3.2 Monetary Theory

Each school of economics

A currency is value on motion

3.4 Money Configuration

Once we have defined value, we need to fund a vehicle to move value around. A currency is value on motion

| Category | Aspect | |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Peg | To same definition of value |

| Collateral | Back this value | |

| Transport Mechanism | Physical | |

| Digital | ||

| Environment | Competition | With similar monetary configurations |

| Coexistence | With different monetary configurations |

3.5 Functions of Money

Aristotle (384–322 BCE). Early thoughts on the functions of money (medium of exchange, store of value, unit of account).

| Purpose | Functions | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Market | Medium of Exchange | A medium of exchange is the set of assets in an economy that people regularly exchange for goods or services. |

| Unit of Account | Money provides a standard unit for measuring and comparing the value of different goods and services. | |

| Store of Value | Money serves as a repository of wealth, allowing individuals to store their purchasing power for future use. | |

| Standard of Deferred Payment | Money enables long-term contracts (loans, rents) by providing a stable repayment benchmark. | |

| Planning | Instrument of State Policy | Bullion reserves financed warfare, navies, and colonization. Monarchs debased coins in crises but generally preferred hard currency (gold/silver) for stability. |

| Tool of Power & Distribution | Money is not neutral—it affects real economic outcomes (unemployment, inequality). Access to credit determines who can invest (reinforcing capitalist hierarchies). Sovereign currency-issuing states (e.g., U.S., Japan) face no solvency constraint, but inflation risks remain. | |

| Tool of Fiscal Policy | Money is a public monopoly used to achieve full employment and price stability. Sovereign currency issuers (e.g., U.S., Japan) cannot run out of money but must manage inflation. Job Guarantees: MMT advocates using money creation to fund public employment, stabilizing demand without causing inflation. | |

| Means of Tax Settlement | Money’s value is sustained because the state demands it for tax payments. This "taxes-drive-money" approach (from Georg Friedrich Knapp’s chartalism) contrasts with commodity or credit theories. | |

| Welfare | Distribution of National Income | |

| Maximization of Satisfaction | ||

| Liquidity to Wealth | ||

| Guarantor of Solvency | ||

| Bearer of Options |

https://drrajivdesaimd.com/2022/07/01/money/

3.6 Function: Medium of Exchange

3.6.1 Authors

A medium of exchange is the set of assets in an economy that people regularly exchange for goods or services. A medium of exchange has two key features: First, it represents a part of its owner's assets; second, it is commonly accepted in transactions. We refer to medium of exchange as the set of assets in an economy that people regularly exchange for goods and services. The use of money as a medium of exchange promotes economic efficiency by eliminating much of the time spent in exchanging goods and services.

The most critical function, as money emerges to solve the double coincidence of wants problem in barter.

Carl Menger (founder of the Austrian School) explained that money arises naturally as the most salable good—one that is widely accepted in trade.

Ludwig von Mises’ Regression Theorem further argues that money must have originated from a commodity with pre-monetary demand (e.g., gold, silver), not by government fiat.

3.6.2. Physical Requirements

| Quality | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Required | ||

| Fungible/Uniform | Say | all parts are equal to each other, that two equal weights of the medium share the same value |

| Divisible | Adam Smith, Say, Rothbard [0] | easy to divide up in smaller parts or put them together to larger parts |

| Stable (Short Term) | Adam Smith, Say, Rothbard [0] | we can store it and it won’t age with time |

| Scarce | Say | total supply of the medium is limited and known |

| Optional | ||

| Acceptable | ||

| Recognizable | ||

| Unforgeable | ||

3.6.3 Digital Requirements

These principles must be provided in the contract.

| Quality | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Required | ||

| Secure | must be secure. | |

| Decentralized | must be decentralized enough to guarantee holders and users the promised behaviour. | |

| Optional | ||

| Compliant | can comply with the regulations in all stages of their value chain in the areas where it is deployed. | |

| Private | must include a privacy capability so the issuer can make use of it according to the regulation in place. This must be an optional property to prevent a conflict with compliance. | |

| Transparent | can provide ability to get disclosures at any moment of their current features and configuration. | |

| Upgradeabie | can be upgradeable during the learning period to allow accomodating new changes. This upgradeability must be protected by mechanisms as DAO gobernance to prevent a conflict with decentralization. | |

However, as the principles maybe change between regions or underlying assets a degree of configuration must be also included.

3.7 Function: Unit of Account

The value of a coin used as an unit of account could also be different from that of the same coin in circulation, a phenomenon referred to as “ghost money” or “imaginary money” (Cipolla 1956; Einaudi 1937, 1953; Sargent and Velde 2002). Einzig (1966) reports on primitive cultures in which people apparently first converged on one or a few commodities as unit of account before converging on one or a few as medium of exchange (similarly, Moini 2001, pp. 284-86). Barter, though continuing, was facilitated by valuing traded goods in the numéraire commodity, instead of keeping track of separate exchange ratios between the two goods in each possible transaction. The numéraire also facilitated valuing unilateral transfers, induding compulsory and traditional ones. Temporal precedence of the numéraire over the medium-of-exchange function is far, however, from a universal historical facto.

Technically, a unit of account is something that is divisible, fungible, and countable. If the money is unique it can fullfill the function of accounting the price of the asset that is exchanged. However, if there is a competition of currencies, it cannot account by tiself the relative prices between good and services and needs the help of a Numéraire.

A unit of account can coexist with multiple media of exchange. The euro existed only as a unit of account for three years before its notes and coins went into circulation in 2002, the old national currencies meanwhile continuing as media of exchange.

3.7.1. Authors

3.7.2. Applications

Money allows for economic calculation by providing a common denominator for comparing prices. Prices expressed in money terms enable entrepreneurs to assess profit/loss, allocate resources efficiently, and coordinate production in a complex economy. Friedrich Hayek stressed that money prices transmit information about scarcity and demand.

3.7.3. Physical Requirements

| Quality | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Divisible | ||

| Fungible | Identical units (e.g., one dollar = another dollar). | |

| Countable | ||

| Stable (Medium Term) | Prices must remain relatively predictable (hyperinflation destroys this). |

3.8 Function: Store of Value

Money also functions as a store of value; it is a repository of purchasing power over time. A store of value is used to save purchasing power from the time income is received until the time it is spent. This function of money is useful because most of us do not want to spend our income immediately upon receiving it but rather prefer to wait until we have the time or the desire to shop. Commodity money has an exchange value because if not used as money it can be used as a commodity.

Money enables individuals to save and defer consumption.

However, Austrians recognize that money is not a perfect store of value due to inflation (central bank expansion) or deflation (contraction of money supply).

Unlike Keynesians, Austrians argue that hoarding money can be rational (e.g., during uncertainty) rather than harmful to the economy.

3.8.2. Authors

For Carl Menger money emerges naturally as the most marketable commodity, serving as a medium of exchange and store of value. ("Principles of Economics" (1871)). Emphasized that money must be durable, widely accepted, and hold stable value to function effectively.

For Ludwig Von Mises, money’s role as a store of value depends on its purchasing power stability. ("The Theory of Money and Credit" (1912)*)

In "Denationalisation of Money" (1976), Hayek argued that sound money (e.g., commodity-backed or competitive currencies) is necessary for long-term value storage.

Jörg Guido Hülsmann Supports commodity money (e.g., gold, silver) as an ethical and stable store of value. (The Ethics of Money Production" (2008)*)

Milton Friedman In "A Monetary History of the United States" (1963), Friedman emphasized that money must retain its purchasing power over time to be an effective store of value. He argued that stable monetary policy (avoiding inflation/deflation) is crucial for money to preserve wealth.

John Maynard Keynes In "The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money" (1936), Keynes discussed money's role as a store of value, particularly in times of uncertainty. He noted that people hold money (liquidity preference) as a safe asset, but inflation erodes its value, making alternative stores (like bonds or gold) preferable.

Karl Marx (Political Economy) In "Das Kapital" (1867), Marx analyzed money as a hoardable commodity (like gold) that must retain intrinsic value to function as a store of wealth.

3.8.3. Physical Requirements

| Quality | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Durable | ||

| Scarce | ||

| Liquid | easily convertible into goods/services without loss. | |

| Stable (Long Term) |

3.8.4. Digital Requirements

| Quality | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Required | ||

| Secure | not subject to any hack | |

| Decentralized | no one, even the issuer, should be able to interfere its behaviour | |

| Optional | ||

| Transparent | disclose all the required information to issuers, holders and regulators. | |

3.9 The Hierarchy of Functions

The 3 canonical functions are enough to deliver the derived functions. So we should bother about how the currency delivers the 3 canonical functions.

3.9.1 Derived Credit Functions

Standard of Deferred Payment

i.e. Credit

3.9.2 Derived Planning Functions

3.9.3 Derived Wealth Functions

4. The Monetary Standard

4.1 Requirements for Money Funcions

The main challenge to have a retail currency is to provide credit without volatility.

4.2 Physical Requirements

| Type | Function | Requirement | Description |

| Physical | Medium of Exchange | Portable | |

| Acceptable | |||

| Divisible | easy to divide up in smaller parts or put them together to larger parts | ||

| Fungible | all parts are equal to each other, that two equal weights of the medium share the same value | ||

| Unit of Account | Contable | ||

| Divisible | |||

| Fungible | |||

| Store of Value | Durable | ||

| Liquid | |||

| Common | Scarce | total supply of the medium is limited and known |

4.3 Digital Requirements

| Type | Function | Requirement | Description |

| Digital | Common | Secure | |

| Decentralized | must be decentralized enough to guarantee holders and users the promised behaviour. | ||

| Private (Optional) | |||

| Compliant (Optional) | must comply with the regulations in all stages of their value chain in the areas where it is deployed. | ||

| Transparent (Optional) | should provide ability to get disclosures at any moment of their current features and configuration | ||

| Upgradeability (Optional) |

4.4 Economic Requirements

4.4.1 Currency Stability

Most of authors mentions Stability as a requirement for the currency. Different Money functions need different level of stability.

| Type | Function | Requirement | Description |

| Economic Requirements | Medium of Exchange | Stable (Short Term) | |

| Unit of Account | Stable (Medium Term) | ||

| Store of Value | Stable (Long Term) |

4.4.2 Currency Stability Principles

By inspecting the principles argued for stability on the schools that advocated for sound money, we find:

| Principle | Description | Authors |

| Market Discipline | No manipulation | |

| No Inflation | Always harmful (Cantillon effects) | |

| Deflation | Natural if market-driven | |

| Convertibility | Must be redeemable. | |

| Underlying Asset | Stability of the currency depends on the stability of the pegged asset |

4.5 Known Money Configurations

4.5.1 Barter

Before money, there was barter. Goods were produced by those who were good at it, and their surpluses were exchanged for the products of others. Every product had its barter price in terms of all other products, and every person gained by exchanging something he needed less for a product he needed more. The voluntary market economy became a latticework of mutually beneficial exchanges. In barter, there were severe limitations on the scope of exchange and therefore on production. This crucial element in barter is what is called the double coincidence of wants. A second problem is one of indivisibilities. [0]

https://www.bis.org/review/r250728i.htm

4.5.2 Physical Proposals for Money

Trying to overcome the limitations of barter, commodity began to be used as a medium of exchange. When a commodity is used as a medium for most or all exchanges, that commodity is defined as being a money. [0] Money made up of some valuable commodity is called commodity money, and from ancient times until several hundred years ago commodity money functioned as the medium of exchange in all but the most primitive societies. The problem with a payments system based exclusively on commodities is that such a form of money is very heavy and is hard to transport from one place to another.

|  |  |  |  |

| Barter | Commodity | Representative | Standard | Fiat |

Once a commodity has been widely accepted for exchanges, it may take on a value as money that is independent of the value of the commodity of which it is composed. At the extreme, what can be called token money may have no commodity value whatsoever. It may also be called representative money in the sense that represents or be a claim on the commodity. Representative money that has no intrinsic value, but is a certificate or token that can be exchanged for the underlying commodity.

As a monetary economy evolved, a particular commodity (e.g. gold) came to become generally accepted as a reference to express all prices in terms of units of that commodity. This was the advent of the monetary standard. At this stage banks began to appear which issued paper substitutes for gold, and these paper substitutes—notes and deposits—had the advantage of being easier to store and move around. These advantages led to notes and deposits gradually replacing gold as media of exchange, but they continued to be expressed in terms of units of gold and to be redeemable on demand into gold. Gold therefore continued to be the monetary standard even though it gradually lost its role as a medium of exchange. [9]

4.5.3 Digital Proposals for Money

|  |  |  |  |

| Unbacked | Utility | Security | Stablecoins | NFT |

4.5.4 Digitalization Equivalences

| Unbacked | Utility | Scientific Planning | Security | Representative | Asset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | IoU | Fidelity Tokens | Fiat | Bonds / Stocks | Representative / Gold | Barter |

| Digital | Memecoins | Utility Tokens | Stablecoins | Security Tokens | ??????? | NFT |

4.6 Functions on Money Configurations

Ability of Known Configurations to Deliver Money Functions

In the modern fiat-money system, the two functions of money—medium of exchange and unit of account—happen to coincide. However, there is wide agreement that there existed a dichotomy between the medium of exchange (e.g., silver coin) and the unit of account (or “money of account”) in the commodity-money system; see, for example, White (1984), Glassman and Redish (1988), Rolnick, Velde and Weber (1997), Redish (2000), Sargent and Velde (2002), and Velde (2009). Indeed, historically, units of account preceded media of exchange in the sense that units of weight, such as the talent and the shekel, evolved into medium-of-exchange units when coins were minted that had specified relations to the weight (Shiller 2002). [50]

| Money Configurations | Monetary Requirements | Monetary Functions | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Economic | |||||||||||||

Portable | Acceptable | Divisible | Fungible | Contable | Durable | Liquid | Scarce | Stable ST | Stable MT | Stable LT | MoE | UoA | SoV | |

| Physical Money | ||||||||||||||

| Barter | NO | NO | NO | NO | ||||||||||

| Commodity | Bad | YES | YES | |||||||||||

| Representative | Bad | YES | YES | |||||||||||

| Fiat | YES | YES | Bad | |||||||||||

| Digital Money | ||||||||||||||

| Unbacked Tokens | YES | NO | NO | |||||||||||

| Utility Tokens | YES | NO | NO | |||||||||||

| Bitcoin | YES | NO | YES | |||||||||||

| Monero | YES | NO | YES | |||||||||||

| Security Tokens | NO | NO | YES | |||||||||||

| Stablecoins | YES | YES | Bad | |||||||||||

| NFTs | NO | NO | NO | YES | ||||||||||

Barter is not money and does not fullfill any of Money Functions

Unbacked Tokens and Utility Tokens work as Medium of Exchange but do not work as Unit of Account or Store of Value. Some utility tokens as Bitcoin or Monero can be used as Store of Value.

Security Tokens and NFT only work as Store of Value

Stablecoins and Fiat Money can be used to transfer value as Medium of Exchange and can be used to account value as Unit of Account. But they do not perform well persisting value so hey are not good Stored of Value.

Finally, Commodity Money and Representative Money are good as Unit of Account and Store of Value but they are not optimal as Medium of Exchange.

So there is not, as today, a Money Configuration which is optimal on delivering the 3 Funcions of Money.

4.7 Monetary Architecture per School

| Money Functions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schools | Theory of Value | Money Configuration | Market | Planning | ||||||

| MoE | UoA | SoV | DP | SP | TP | FP | TS | |||

| Scholastics | Subjective | Sound | 1 | 2 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Mercantilism | Objective | Fiat | 2 | 3 | 1 | - | 4 | - | - | - |

| British Empiricism | Subjective | Sound | 1 | 2 | 3 | - | 4 | - | - | - |

| Physiocrats | Objective | Sound | 1 | 2 | 3 | - | - | - | 4 | - |

| Classical | Objective | Sound | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| Marxist | Objective | Sound | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | - | - | - |

| Neoclassical | Subjective | Fiat | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| Austrian | Subjective | Sound | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| Keynesian | Subjective | Fiat | 1 | 3 | 2 | - | 4 | - | - | - |

| Monetarism | - | Fiat | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | - | - | - | |

| Post-Keynesian | Subjective | Fiat | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | - | 5 | - | - |

| MMT | Subjective | Fiat | 2 | 1 | 3 | - | - | - | 4 | 5 |

4.8 The Monetary Ecosystem

Market, institutions, banks, government, networks.... it depends

4.9 The Social Order

4.9.1 Rational Expectations

SocialOrder - Robert Lucas (1937–2023). Rational Expectations Theory – people adjust to monetary policy. Lucas Critique – policy changes alter expectations.

THE EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

Reverse engineering the social order created by each currency configuration.

5. The Spontaneus Order

5.1 Contributors

| School | Authors / Ideas |

|---|---|

| Scholastics / School of Salamanca 1100s-1600s | Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) / Francisco de Vitoria (1483–1546), Martín de Azpilcueta (1492–1586), Juan de Mariana (1536–1624) |

| Subjective value, sound money | |

| British Empiricism 1690-1770s | John Locke (1632-1704), David Hume (1711—1776) |

| Subjective value, sound money | |

| Physiocracy 1759-1775 | Richard Cantillon (1680–1734), François Quesnay (1694–1774), Tha Marquis da Mirabeau (1715–1789), Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) |

| Objective value (land), sound money | |

| Classical 1770s-1870s | Adam Smith (1723-1790), Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834), Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832), David Ricardo (1772–1823), John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) |

| Objective value, Long-run money neutral, sound money | |

| Austrian School 1871–1980s | Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850), Carl Menger (1840-1921), Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851–1914), Friedrich Von Wieser (1851-1926), Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973), Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883-1950), Henry Hazlitt (1894–1993), Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992), Murray N. Rothbard (1926-1995) |

| Subjective value, money no neutral, sound money / currency competition | |

| New Austrian School 1980s–present | Israel Kirzner (1930), Antal E. Fekete (1932), Hans-Hermann Hoppe (1949), Joseph T. Salerno (1950), Lawrence H. White (1954), Huerta de Soto (1956), George A. Selgin (1957), Steven Horwitz (1964-2021) |

| Subjective value, money no neutral, sound money / currency competition |

5.2 Principles

5.2.1 Negative Liberty

Property Rights

Free Will

Methodological Individualism

All social phenomena (markets, institutions, prices) must be explained by reference to the actions, choices, and intentions of individuals, not abstract groups or aggregates.

5.2.2 Human Action

The concept of "spontaneous order" is the idea that complex, functional systems emerge organically from decentralized human actions, without central design, is a cornerstone of Austrian economics and classical liberal thought.

Adam Smith (1723–1790) argues that The "invisible hand"—markets coordinate self-interested actions into social benefit in The Wealth of Nations (1776). "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest."

Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) says that "The market is a process, actuated by the interplay of the actions of the various individuals cooperating under the division of labor." Human Action (1949).

Praxeology

5.2.3 Normative Economics

5.3 Sound Money

Adam Smith (1723–1790). In "The Wealth of Nations," discussed money as a facilitator of trade. Argued for commodity-backed money (gold/silver).

David Ricardo (1772–1823). Advocated for the Gold Standard. Developed theories on inflation and currency stability.

5.3.1 Variants of Sound Money

https://www.hardmoneyhistory.com/types-of-gold-standard/

file:///home/pellyadolfo/Downloads/03Chapter3%20(1).pdf

5.3.2 Commodity Money

| Region | Commodity Money |

|---|---|

| Ancient Period | Copper Unit of Account in Ancient Egypt, Barley and Silver Money of Babylonia and Assyria, Sealed Ingots in Cappadocia, Sheep and Silver Currency in the Hittite Empire, Livestock and Weighed Silver Money of the Jews, Delayed Adoption of Coinage in Phoenicia and Carthage, Invention of Coinage in Lydia, Livestock Standard in Ancient Persia, Ox and Base Metal Currencies in Greece, Crude Bronze Currency of Pre-Roman Italy and Rome, Bronze Axes and Wheels as Currencies in Gaul, Cattle Currency of the Ancient Germans, Iron Sword Currency of Britain, Slave Girl Money of Ireland, Cattle Currency of India, Shell, Silk and Metal Currencies of China |

| Medieval Period | Rings and Weighed Metal Currencies of the British Isles, Cattle Money in Ireland, Cattle, Cloth and Weighed Metal Money in Germany, Leather Currency in Italy and France, Cattle, Cloth and Fish Currency of Iceland, Ring Money of Denmark, Cattle and Cloth Currency of Sweden, Butter as Currency in Norway, Calves as Monetary Unit in Hungary, Fur Money of Russia, Cowries as Currency in India, Livestock Standard of the Mongols, Salt Money of China, Gold Dust Money of Japan |

| Modern Period | Leather Money of the British Isles, Cattle Currency of Ireland, Rum Currency in Australia, Fur and Wheat Currency in Canada, Sugar Money of Barbados, Tobacco Money of the Bermuda, Tobacco and Sugar Money of the Leeward Islands, Mahogany Logs as Currency in British Honduras, Uncoined Silver Money in Russia, Grain Money in France, Commodity Units of Account in Germany and Austria, Almonds as Currency in India, Fictitious Monetary Unit in China, Rice Money in Japan |

| Oceania | Cloth Money in Samoa, Teeth Currency of Fiji, Stone Money of Yap, Bead Currency of Pelew, Pig Exchanges on the New Hebrides, Feather Money of Santa Cruz, Shell Loans on the Banks Islands, Shell and Teeth Currencies on the Solomon Islands, Intricate Currency of Rossel Island, Teeth on the Admiralty Islands, Shell and Yam Currencies of the Trobriand Islands, The "Sacred" Money of New Britain, New Guinea's Boar Tusk and Shell Currencies |

| Asia | Rice Standard in the Philippines, Drum Currency of Alor, Wax and Buffaloes as Money in Borneo, "Homeric" Currencies in Cambodia, Gambling Counters as Money in Siam, Tin Ingots and Gold Dust in Malaya, Weighed Silver and Lead Currency in Burma, Tea Brick Currency in Mongolia, Coconut Standard on the Nicobars, Grain Medium of Exchange in India, Reindeer and Cattle Standard in Asiatic Russia, Currencies at the Persian Gulf |

| Africa | Iron Currency in Sudan, Salt Money of Ethiopia, Livestock Standard in Kenya, Bead Money of Tanzania, Cowries as Currency in Uganda, Calico Currency in Zambia, Cloth, Metals and Slaves as Currency in Equatorial Africa, Cowrie Crises in the Former French Sudan, Cowries, Slaves, Cloth and Gin Money of Nigeria, Gold Dust Currency of Ghana, Debased Brass Rod Currency of the Congo, Shell Money of Angola, Cattle and Bead Money of South-West Africa, Cattle Currency in South Africa |

| America | Fur Currency in Alaska, Shell, Fur and Blanket Currency of Canada, Wampum and Other Shell Currencies in the United States, Cocoa Bean Currency of Mexico, Maize Money of Guatemala, Cattle Standard in Colombia, Arrows and Guns as Currency in Brazil, Snail Shell Currency in Paraguay |

5.3.3 Representative Money

Representative money or token money is any medium of exchange that represents something of value, typically a commodity.

Earlier classifications in the history of money made of the useful distinction between money of “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” value. Intrinsic fall-back value of token money is virtually zero as a commodity. At the other extreme, the value of representative money is inherited for the represented commodity. Value on a commodity by the esteem in which it is held as measured by outside valuations that relate demand to supply, i.e., by scarcity. [32]

The earliest form of representative money consisted of small pieces of leather, usually marked with an offical seal. [-1] It was understood that the certificate could be redeemed by the commodity at any time. Also, the certificate was easier and safer to carry than the actual commodity. Over time people grew to trust the paper certificates as much as the commodity.

There is no concrete evidence that the clay tokens used as an accounting tool to keep track of warehouse stores in ancient Mesopotamia were also used as representative money.However, the idea has been suggested. [32]

The introduction of coinage, or metal based representative money, marks an important innovation in the history of money and a transition in the development of civilization itself. Coinage was probably invented in Asia Minor in the seventh century BC and it rapidly spread throughout the Mediterranean area. The earliest coins were made of electrum and had punch marks and some kind of identifying device. [32]

Paper currency first developed in Tang dynasty China during the 7th century, where it was called "'flying money'", although true paper money did not appear until the 11th century, during the Song dynasty. The use of paper currency later spread throughout the Mongol Empire or Yuan dynasty China. European explorers like Marco Polo introduced the concept in Europe during the 13th century.

Today, gold or silver certificates, for example, which are claims on precise amounts of gold or silver, could be also called representative money.

The advent of blockchain technologies and programmable money in 2009 provides a novel support for representative money with enhanced features, as we will discuss in this document.

https://mises.org/podcasts/minor-issues/who-invented-money

5.3.4 Regression Theorem

The Regression Theorem, first proposed by Ludwig von Mises in his 1912 book The Theory of Money and Credit, states that the value of money can be traced back ("regressed") to its value as a commodity.

5.3.5 Purchasing Power

5.3.6 Evaluation of Functions

5.4 The (Real) Market Process

5.4.1 A Self-Regulated System

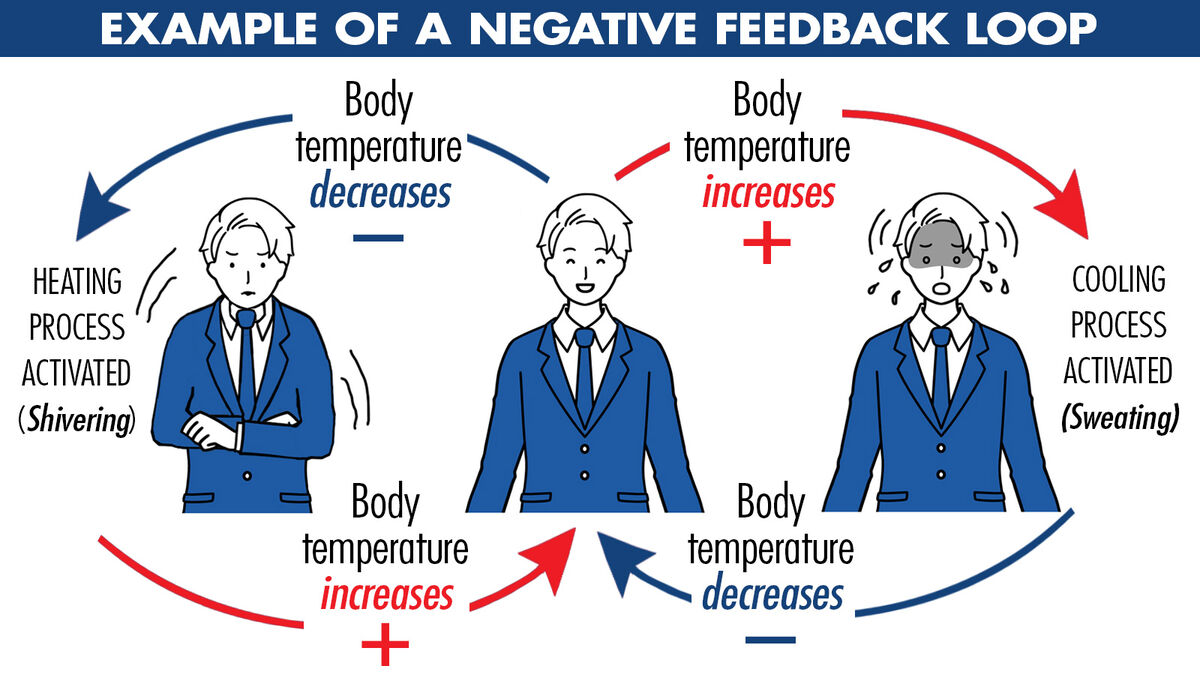

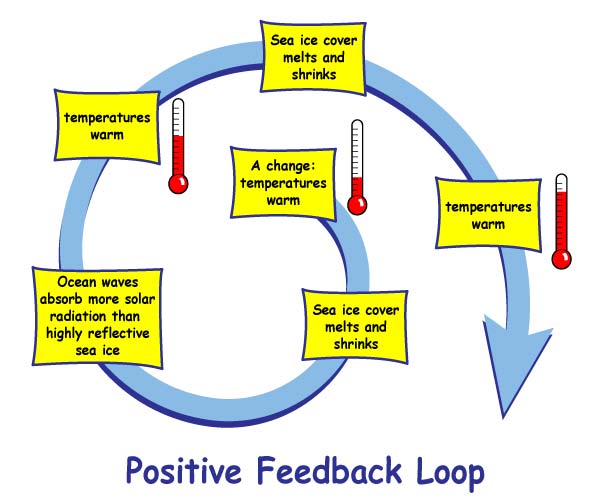

In a regulated system, the output is somehow modified and injected to the input. This backwards injection is called a feddbackp loop.

5.4.2 Supply Side

Heterogeneity of Commodities. Even "identical" commodities (e.g., wheat, oil) differ in time, place, and quality. Lachmann’s Capital Theory: Commodities are multi-specific—their usefulness depends on the production plan.

Commodities have no intrinsic value—their worth depends on individual needs and marginal utility. Example: Water is more valuable to a thirsty hiker than to someone beside a lake.Implication: Prices emerge from voluntary exchanges, not labor costs (vs. Marx) or physical properties.

Critical Resources

Entrepreneurial Discovery (Kirzner). Entrepreneurial Coordination (Kirzner’s alertness). Entrepreneurs discover gaps in production (e.g., unmet demand, inefficiencies) and adjust. Entrepreneurship Drives Adjustment. Kirzner’s "Alertness": Entrepreneurs discover profit opportunities (disequilibrium gaps) and correct them.

Savings

Theory of Capital. Structure of Capital. While classical economists laid groundwork, Böhm-Bawerk is most credited with formalizing the Austrian theory of capital—emphasizing time, heterogeneity, and subjective value. Hayek later refined it into a full intertemporal structure theory, distinguishing Austrian capital theory from mainstream approaches. Böhm-Bawerk’s roundaboutness: Time preference drives capital structure. Lachmann’s heterogeneous capital: Plans constantly change, causing economic shifts. Neglect of capital theory: Many modern Austrians focus on macro/money instead. Austrian View: Capital goods are idiosyncratic, complementary, and tied to specific production plans. Time & Uncertainty Matter. Böhm-Bawerk’s "Roundabout Production": Capital structure depends on intertemporal coordination (matching savings with long-term investment).

Production In Austrian economics, production is not a mechanical input-output system (as in neoclassical models) but a dynamic, time-consuming, and entrepreneurial process shaped by subjective valuations, capital heterogeneity, and market prices. The Structure of Production (Böhm-Bawerk’s roundaboutness).

Supply of Goods and Services is Constrained by Real Resources (Not Just Prices). Labor, capital, and raw materials are heterogeneous (not interchangeable).

5.4.3 Market Coordination

Catallactics is the science of how free people trade—and why that process cannot be replaced by coercion or central planning. In Austrian economics, the term "catalactics" (from the Greek katallattein, meaning "to exchange" or "to reconcile") refers to the study of market exchanges as the foundation of economic science. Unlike mainstream economics, which often focuses on mathematical models and aggregate variables, Austrians emphasize human action, subjective value, and the dynamic process of voluntary trade. Ludwig von Mises popularized the term in Human Action (1949), defining catallactics as: "The analysis of those actions which are conducted on the basis of monetary calculation … the science of the market economy." Richard Whately (19th-century economist) first coined the term to distinguish economics as the study of exchange rather than wealth or production.

Demand of Goods and Services arises from individual valuations—each person ranks goods based on marginal utility (Menger’s Principles of Economics, 1871). In Austrian economics, market demand is not a static, aggregate curve (as in neoclassical models) but a dynamic, subjective, and individual-driven process. Austrians reject the idea of "aggregate demand" as a measurable or policy-controllable variable, instead focusing on how real human preferences, prices, and entrepreneurial discovery shape demand. Demand as Subjective Value (Not a "Demand Curve") Demand is Decentralized & Dispersed. No central planner (or economist) can know or measure "total demand"—it exists only as individual choices revealed through action. Demand is Intertemporal. People don’t just demand goods now but also future goods (savings vs. consumption trade-offs). Böhm-Bawerk: Low interest rates artificially boost demand for long-term projects (leading to malinvestment). Demand is Constrained by Real Income (Not Money Printing). Inflation (e.g., stimulus checks) may raise nominal demand but distorts real resource allocation (Cantillon effects). Entrepreneurship Discovers Demand. Entrepreneurs anticipate unmet demands (Kirzner’s alertness), creating new markets (e.g., smartphones). Demand is not a curve but individuals acting on preferences For Austrians, market demand is a discovery process

Time Preferences Time Preference Drives Production Length. Low time preference (people save more) → longer, more productive processes. High time preference (people consume now) → shorter, less efficient production. Mises: "Capital is accumulated by saving, which requires deferred consumption."

Price Formation price formation in a self-regulated system. Emerge from trial & error. Prices reveal demand. No central director is needed—prices and profits guide decentralized coordination. Profit & Loss Guide Production: Profits signal correct production decisions. Losses reveal waste, prompting reallocation. For Austrians, production is a discovery process—never perfectly efficient, but constantly adapting via market signals.

5.4.4 The Price System

Hayek’s "Use of Knowledge in Society" (1945). Prices synthesize dispersed information (preferences, scarcity, costs) into a single metric. Example: A rising copper price signals scarcity, prompting producers to mine more and consumers to economize. Prices as Information Signals (Hayek). Knowledge is Dispersed & Subjective. Hayek’s Knowledge Problem: No single entity (e.g., central planners) can access all market information. Prices emerge from decentralized individual action

Relative Prices

Price System Required to enable subjective value. If we ignore price system and rely on underlaying value, it is objective value, In Austrian economics, the price system is not a static equilibrium mechanism (as in neoclassical models) but a dynamic, decentralized communication network that coordinates knowledge, guides production, and adjusts to disequilibrium. Unlike mainstream theories. Price Signals as Knowledge Coordinators. Prices distill and communicate dispersed information about relative scarcities and values. The price system allows society to utilize knowledge no single mind possesses. Example: Rising copper prices signal scarcity, prompting conservation and increased production

Economic Calculation Without private property, prices cannot form → economic chaos (Mises’ 1920 critique). No "Equilibrium. Mises & Hayek: The economy is a continuous process, not a state of balance. "The market is never at rest" (Ludwig von Mises, Human Action).

Disequilibrium Analysis (Mises-Hayek’s critique of equilibrium models). The Austrian School fundamentally rejects the neoclassical focus on static equilibrium models, instead emphasizing disequilibrium as the natural state of markets. Austrian economists analyze how markets coordinate knowledge, correct errors, and adapt to change through dynamic processes driven by entrepreneurship, time, and uncertainty. For Austrians, disequilibrium is the norm—markets work precisely because they are never in balance, but constantly discover, adapt, and correct.

Profit and Loss System Acts as continuous feedback mechanism for resource allocation. Profits indicate valued uses; losses signal misallocation. Example: Movie box office results guide future film production investments

Allocation of Resources the Austrian School views resource allocation as: A Discovery Process - Resources find their most valued uses through entrepreneurial competition and market experimentation Decentralized and Emergent - No single entity can possess all the knowledge needed for "optimal" allocation Time-Structured - Allocation occurs through multi-stage production processes Price-Guided - Market prices serve as the essential signals for allocation decisions

Private Projects Risk

5.4.5 Value Chain

Production doesn’t happen instantly but through stages:

Higher-Order Goods (raw materials, machines, factories).

Lower-Order Goods (final consumer products).

5.4.6 System Self-Regulation

Market itself, if not distorted, is a well performing price formation machine. A CryptoCommodity have a built-in self-regulation since customers provide a negative feedback loop regarding the quality of the currency. If the currency does tno fullfill the expected quality, the demand for the CryptoCommodity is reduced. This is Adam's Smith Invisible Hand.

Negative feedback (or balancing feedback) occurs when some function of the output of a system, process, or mechanism is fed back in a manner that tends to reduce the fluctuations in the output, whether caused by changes in the input or by other disturbances. A classic example of negative feedback is a heating system thermostat — when the temperature gets high enough, the heater is turned OFF. When the temperature gets too cold, the heat is turned back ON. In each case the "feedback" generated by the thermostat "negates" the trend.

5.5 Monetary Policy

The gold standard is still prone to collapse caused by malinvestments fueled by government intervention.

5.5.1 Classical Economics (1776–1870)

Classical Economics (1776–1870) the dominant economic school was the Classical School, with strong influences from laissez-faire economics and the Banking School vs. Currency School debates in Europe. System Stability on malinvestments. It started on 1776 when Smith published Wealth of Nations which marked the decline of mercantilism.

| Post-American Revolution Economic Crisis (1780s–1790s) | To finance the Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the Continental Congress printed "Continental Dollars" with no gold/silver backing. By 1781, rampant money-printing led to hyperinflation ("Not worth a Continental"). Prices soared, savings evaporated, and the currency collapsed. The U.S. federal government (under the Articles of Confederation) had no power to tax, so it relied on debt and IOUs. States issued their own unbacked paper currencies, creating monetary chaos. |

| The Panic of 1796–1797 (UK & U.S.) | The Bank of England (BoE) suspended gold convertibility in 1797 due to gold shortages caused by the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802). The British government borrowed heavily from the BoE, leading to inflation of paper money. The First Bank of the United States (1791–1811) expanded credit, fueling land speculation. |

| Panic of 1819 (U.S.) | The Second Bank of the United States (SBUS) (a quasi-central bank) lowered interest rates, fueling malinvestment in land and agriculture. When the SBUS tightened money, overextended businesses collapsed. |

| Panic of 1837 (Global, especially U.S. & UK) | President Andrew Jackson vetoed the recharter of the Second Bank of the U.S. (1832) and moved federal deposits to state banks ("pet banks"). State banks issued excessive paper money unbacked by specie. |

| 1847 UK Financial Crisis | The Railway Mania (1843–1846) saw wild speculation in British railroads, fueled by easy credit. Investors borrowed heavily to buy shares, expecting endless profits. The Bank of England’s low interest rates and private bank lending created a false boom. |

| Panic of 1857 (Global, particularly U.S. & Europe) | The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) increased the money supply, lowering interest rates artificially Causing malinvestment in railroads. |

| 1866 Overend Gurney Crisis (UK) | The 1866 British financial crisis - centered around the collapse of Overend, Gurney & Co. As a quasi-bank, Overend operated on fractional reserves, unable to meet obligations when confidence faltered. Bank of England injected liquidity to prevent systemic collapse. |

| Long Depression (1873–1896, Global) | The U.S. was on a de facto gold standard, but the Sherman Silver Purchase Act (1890) required the Treasury to buy large amounts of silver and issue notes redeemable in both gold and silver (bimetallism). This created uncertainty about whether dollars would be redeemed in gold or depreciated silver. Fractional Reserve Banking: Banks issued more loans to roads ad farmers than they could cover with gold reserves, making them vulnerable to panics (Rothbard’s critique of unbacked credit). President Grover Cleveland repealed the Sherman Silver Act (1893) to stop gold outflows but failed to restore confidence immediately. The Treasury issued bonds to replenish gold reserves (a bailout of sorts). The depression lasted until 1897, with unemployment reaching 20%. |

| The Baring Crisis (1890, UK & Argentina) | The Baring Brothers bank nearly collapsed due to overexposure to Argentine debt. Banks took excessive risks knowing the Bank of England would bail them out. |

| Panic of 1907 (U.S.) | U.S. banks operated on a fractional reserve system. When depositors lost confidence, bank runs began. The Klondike Gold Rush (1896–1899) and gold discoveries in South Africa increased the U.S. money supply. This led to lower interest rates, fueling stock market and real estate speculation. When gold inflows slowed, credit tightened, exposing overleveraged trusts and banks. |

5.5.1 Neoclassical Roaring Twenties (1920–1929)

Neoclassical Economics Ruled (1890s–1920s) with strong remnants of Classical Laissez-Faire ideology:

The Roaring Twenties (1920–1929) were fueled by a unique mix of monetary policy, technological innovation, debt-driven speculation, and post-war economic shifts—even though the U.S. had technically restored the gold standard after WWI. Here’s what drove the boom before the 1929 crash:

- (1) Easy money on 1917-1919 out of gold standard

- (2) The Fed kept interest rates artificially low (even after returning to gold de jure in 1919) to: Help Europe (especially Britain) stabilize its post-war economy. Avoid deflation (which had caused the 1920–21 depression). Result: Easy money → cheap credit → stock and real estate speculation.

- (3) Andrew Mellon’s tax cuts (top rate dropped from 73% to 25%) boosted investor confidence. Laissez-faire regulation allowed unchecked corporate growth and stock manipulation.

- (4) Global Gold Flows to the U.S. Post-WWI, the U.S. held over 40% of the world’s gold reserves (Europe was drained). This allowed the Fed to print more dollars without immediate inflation (gold inflows offset money growth).

- (5) Fractional Reserve

Panic of 1929 (US). The Fed raised interest rates in 1928–29 to curb speculation, making borrowing more expensive and reducing liquidity. This policy strangled economic growth just as the bubble was peaking.

5.5.1 Keynesian Bretton Woods (1944–1971)

The Bretton Woods system (1944–1971) was primarily shaped by Keynesian economics, though it also incorporated elements of classical liberalism and pragmatic internationalism. Here’s how different schools influenced it:

-

Dominant School: Keynesian Economics. John Maynard Keynes (UK) was the most influential economist at Bretton Woods. His ideas on managed capitalism, fiscal stimulus, and avoiding deflation shaped the system. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank were designed with Keynesian principles in mind: Exchange rate stability (pegged but adjustable rates) to avoid competitive devaluations. Capital controls to allow governments to pursue full employment without speculative attacks. Counter-cyclical lending (IMF) to help countries avoid austerity during downturns.

-

Compromise with Classical Liberalism (U.S. Vision) Harry Dexter White (U.S. Treasury) represented a more market-oriented, U.S.-centric approach, influenced by neoclassical and monetarist ideas. The U.S. insisted on: Gold convertibility (dollar pegged to gold, others to the dollar) to maintain discipline. Freer trade (leading to the later General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, GATT). This reflected a belief in open markets, but with Keynesian safeguards.

-

Rejection of Laissez-Faire & Austrian Economics. The Great Depression had discredited gold standard orthodoxy. Bretton Woods explicitly rejected unregulated finance, instead promoting government intervention to stabilize economies.

Legacy: A Keynesian-Embedded Liberal Order The system was a middle ground between socialism and unfettered capitalism, often called "embedded liberalism" (a term coined by John Ruggie).

It collapsed in 1971 (Nixon Shock) when Keynesian policies faced stagflation, giving way to neoliberalism/monetarism under Reagan/Thatcher.

5.5.1.1 Bretton Woods Taxes

Under the Bretton Woods system (1944–1971), tax levels in major economies—particularly the U.S. and Western Europe—were historically high by today's standards, reflecting Keynesian economic policies aimed at funding post-war reconstruction, social welfare, and Cold War military spending. Here’s a breakdown:

- United States: High Top Marginal Tax Rates To fund WWII debt, the Marshall Plan, and the Cold War (military, space race).

- Top Income Tax Rate:

- 1944–1963: 91% (peaked during WWII, remained near this level under Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy).

- 1964: Reduced to 77% (Kennedy-Johnson tax cuts).

- 1971: 70% (Nixon era, just before Bretton Woods collapsed).

- Corporate Taxes: Around 50% (high but with loopholes).

- Capital Gains Tax: 25% (lower than income taxes to encourage investment).

- Western Europe: Even Higher Taxes + Welfare States Post-war rebuilding required massive public investment.

- UK: Top rate over 90% (Labour gov't nationalized industries, built NHS).

- France/Germany: High VAT (value-added taxes) introduced later, but income/corporate taxes were steep.

- Scandinavia: Already adopting high taxes (50%+) to fund universal welfare.

- Developing World: Lower but Rising Taxes

- Latin America/Asia: Taxes were lower (often < 30% top rate), but tariffs and state-owned enterprises played a bigger fiscal role.

- Bretton Woods institutions (IMF/World Bank) encouraged tax reforms to fund development.

5.5.1.2 Fractional Reserve

United States: 10–20% for commercial banks (varied by deposit type). The Fed adjusted reserves to manage credit growth without breaking the gold peg.

Europe: Higher reserves in war-damaged economies (e.g., UK, France) to prevent inflation. Some countries used direct credit controls (limiting loan volumes) instead of just reserve ratios.

Developing Nations: Often had higher reserve ratios (up to 30%) due to weaker banking systems.

5.6 Sound Money Limitations

5.6.1 Small Market

- Limited Credit Availability

- Money Supply limitations

- Supply of Goods Limitations

- Demand of good Limitation

5.6.2 Externalities

5.6.3 No Experimentation

5.6.4 Not a Silver Bullet

Despite using a stable currrency guarantees cantillon effects free, it does not provide stability on malinvestments and users are impacted by malinvestments of other users just because they share the same currency

6. The Scientifically Planned Order

6.1 Contributors

| School | Comments |

|---|---|

| Mercantilism 1500s-1700s | Thomas Mun (1571-1641), Jean Bodin (1529—1596), Charles Davenant (1656 – 1714) |

| Objective value, money non-neutral but supported currency manipulation | |

| Neoclassical 1870s–present | Alfred Marshall (1842-1924), Léon Walras (1834-1910), William Stanley Jevons (1835–1882), Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), Knut Wicksell (1851–1926), Irving Fisher (1867–1947) |

| Subjective value, money neutral, fractional reserve | |

| Keynesian 1936–present | John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), Paul Samuelson (1915–2009) |

| Subjective value, money only neutral on full employment, fiat money | |

| Monetarism 1950s–1980s | Milton Friedman (1912-2007), George Stigler (1911 –1991), Gary Becker (1930-2014) |

| No theory of value, long-run neutrality of money, fiat money with fixed growth | |

| Post-Keynesian 1970s-present | Hyman Minsky (1919–1996), Michal Kalecki (1899–1970) |

| Subjective value, money not neutral, fiat money | |

| New Keynesian 1970s-present | Joseph Stiglitz (1943), Ben Bernanke (1953) |

| Subjective value, money not neutral, fiat money | |

| Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) 1990s-present | L. Randall Wray (1953), Stephanie Kelton (1969) |

| Subjective value, money not neutral, fiat money with government intervention |

6.2 Principles

Positive Liberty

Positive Economics

6.3 The Fiat Standard

6.3.1 The Demand for Money

Keynes’s Liquidity Preference Theory.

Keynesian Revolution – fiscal & monetary policy for demand management.

Baumol-Tobin Model of Transaction Demand for Money

6.3.2 Increasing the Supply of Money

Determinants of Money Supply: Exogenous vs. Endogenous Money

6.3.3 Neutrality of Money

The neutrality of money, also called neutral money, is an economic theory stating that changes in the money supply only affect nominal variables and not real variables. In other words, the amount of money printed by central banks can impact prices and wages but not the output or structure of the economy,w hich means, there is not distortion in relative prices.

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) Critiqued the neutrality of money (short-run non-neutrality).

David Hume (1711–1776). Introduced the concept of neutrality of money in the long run.

6.3.4 Quantity Theory of Money

John Locke, in the late 17th century, developed a precursor to the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM). He argued that the value of money is inversely related to its quantity in circulation. Some economic historians credit him with establishing a sound currency foundation. Locke's ideas, while not a fully developed QTM, laid the groundwork for later economists like David Hume and Irving Fisher, who formalized the theory. Locke's work, particularly in "Several Papers Relating to Money, Interest, and Trade," explored the relationship between the quantity of money and its value. He observed that if a country's money supply increased relative to its trade volume, its prices would likely rise. Locke's core idea was that the value of money is influenced by its supply. He believed that the demand for money was relatively stable and that changes in its supply would impact prices. David Hume (1711–1776). Formalized the Quantity Theory of Money (money supply → price levels).

In contrast to the hesitant qualitative monetary analysis by the economists mentioned above, there is also a current in the economic literature that does not treat qualitative issues at all. This is the simple quantity theory of money. The theory was originally formulated by Nicolaus Copernicus in 1517, whereas others mention Martín de Azpilcueta and Jean Bodin as independent originators of the theory. John Locke studied the velocity of circulation, and David Hume in 1752 used the quantity theory to develop his price–specie flow mechanism explaining balance of payments adjustments. Also Henry Thornton, John Stuart Mill and Simon Newcomb among others contributed to the development of the quantity theory. The quantity theory of money is the heart of neoclassical monetary theory. It has later been discussed and developed by several prominent thinkers and economists including John Locke, David Hume, Irving Fisher and Alfred Marshall. Milton Friedman made a restatement of the theory in 1956 and made it into a cornerstone of monetarist thinking.

The quantity theory of money is most often expressed and explained by reference to the equation of exchange. The equation of exchange was derived by economist John Stuart Mill. The equation states that the total amount of money that changes hands in an economy will always be equal to the total monetary value of goods and services that changes hands in an economy. In other words, the amount of nominal spending will always be equal to the amount of nominal income. The equation is as follows:

where M=Money Supply, V=Velocity of circulation (the number of times money changes hands), P=Average Price Level, T=Volume of transactions of goods and services

The velocity of money is a measurement of the rate at which money is exchanged in an economy. It is the number of times that money moves from one entity to another. The velocity of money also refers to how much a unit of currency is used in a given period of time. Simply put, it's the rate at which consumers and businesses in an economy collectively spend money. The velocity of money is usually measured as a ratio of gross domestic product (GDP) to a country's M1 or M2 money supply.

Alfred Marshall (1842–1924). Developed the Cambridge Cash Balance Approach (money demand = k × PY). Refined the Quantity Theory of Money.

Friedman argued that money supply growth should be stable to prevent inflation or deflation ("Money is a veil" in the long run, but crucial in the short run).

6.3.5 Fractional Reserve

-

Lawrence H. White: Defends free banking with fractional reserves as historically stable.

-

George Selgin Position: Advocates for market-driven FRB under free banking.

-

Steven Horwitz (1964–2021). Position: Supported FRB as compatible with Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) if unregulated.

-

Israel Kirzner (b. 1930) Position: Open to FRB as part of entrepreneurial market processes.

Critics’ Rebuttals (Rothbardians & Hoppe)

Hans-Hermann Hoppe: Argues FRB is always fraudulent because demand deposits imply 100% availability.

Jesús Huerta de Soto: In "Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles" (2006), claims FRB violates property rights (banks lend out deposits they don’t own).

Murray Rothbard: Compared FRB to counterfeiting (banks create fake receipts for nonexistent reserves).

1900–1913 National/State Banking Laws National banks: 15–25% reserves (cash/vault). State rules varied widely. 1913 Federal Reserve Act Tiered reserves: 12–18% for demand deposits, 5% for time deposits. 1920s Fed’s Loose Policy Effective reserves fell due to credit expansion. No formal ratio changes. 1931 Fed Tightens (Depression) Raised reserve requirements, worsening bank failures. 1933 Glass-Steagall Act Strengthened reserves + FDIC insurance to prevent runs.

https://whatismoney.info/fractional-reserve-banking-inflation/

6.3.6 The Money Multiplier

If the reserve ratio (i.e. reserve requirement) is higher, the money multiplier is weaker, and there will be less change to the money supply.

The formula for money supply is MS = (MB x MM). MS is Money Supply MB, or monetary base, is the amount of money in circulation or available to be circulated. MM is money multiplier, which is calculated by dividing 1 by the required reserve set by the Federal Reserve.

6.3.7 Money Aggregates

https://www.tradingpedia.com/forex-academy/monetary-aggregates/

https://ebrary.net/14166/economics/monetary_aggregates_central_banks

JUST IN 🚨: U.S. M2 Money Supply jumps to new all-time high of $22 Trillion 📈📈

M0 = Central Bank Balance Sheet

6.3.8 Layered Money

https://andyjagoe.com/how-to-understand-money/

6.4 Financial Markets

6.4.1 Market Equilibrium Analysis

6.4.1.1 Partial Equilibrium

6.4.1.2 General Equilibrium

In economics, general equilibrium theory attempts to explain the behavior of supply, demand, and prices in a whole economy with several or many interacting markets, by seeking to prove that the interaction of demand and supply will result in an overall general equilibrium. Léon Walras (1834–1910). General equilibrium theory, integrating money into economic models.

New Keynesian Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models

6.4.2 Financial Ecosystem

Money Markets

Capital Markets

Financial Assets

Banks

Corporations

6.4.3 Methodology

Scientific Method

6.5 Monetary Policy

6.5.1 Mercantilism (1492-1766)

6.5.2 Keynesian Flavours (1933-now)

6.5.2.1 Historical Evidence

| School | Comments |

|---|---|

| Neoclassical 1914–1918 | Neoclassical Economics Ruled (1890s–1920s) with strong remnants of Classical Laissez-Faire ideology. During WWI (1914–1918), most nations suspended gold convertibility to print money for war financing, causing inflation and exchange rate volatility. The U.S. suspended gold convertibility in 1917 to fund WWI efforts (following European nations like Britain). The Federal Reserve (established in 1913) printed money freely, causing inflation (~15% in 1918). The United States returned to the gold standard de jure in 1919 (post-WWI) and de facto by 1925, as part of a global effort to restore pre-war monetary stability during the Roaring Twenties. |

| Keynesian Economics (1933–1945) | Transition to Keynesian Economics (1933–1945). Great Depression (1929–1939). FDR took the U.S. off gold in 1933 (Emergency Banking Act), devalued the dollar to $35/oz, and banned private gold hoarding. Keynesian Revolution: John Maynard Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) argued for: Active Central Banking: Monetary policy should stabilize demand (lower interest rates, liquidity injections). Fiscal-Monetary Coordination: Central banks worked with governments (e.g., New Deal, WWII spending). |

| Monetarism (1970s–Early 1980s) | High Inflation & Monetarism (1970s–Early 1980s). Monetarists. Money Supply Growth Targeting. Challenge: Oil shocks (1973, 1979) and loose monetary policies led to stagflation (high inflation + high unemployment). Policy Response: The Fed, under Paul Volcker (1979–1987), adopted monetarist principles (following Milton Friedman) and raised interest rates dramatically (peaking at ~20% in 1981). Focus shifted to controlling money supply growth to curb inflation, even at the cost of a recession. Result: Inflation fell sharply by the mid-1980s, establishing central bank credibility. |

| New Keynesians Mid-1980s–2007 | The Great Moderation (Mid-1980s–2007). Inflation Targeting (New Keynesians). Inflation targeting became the consensus among central banks by the 2000s, blending New Keynesian theory with pragmatic lessons from monetarism. Shift to Inflation Targeting: Central banks (e.g., New Zealand in 1990, followed by the UK, Canada, and others) adopted explicit inflation targets (typically ~2%). The Fed, under Alan Greenspan, focused on price stability while implicitly targeting inflation. Tools: Primary tool: Adjusting short-term interest rates (federal funds rate in the U.S.). Reliance on macroeconomic models (e.g., Taylor Rule) to guide rate decisions. Outcome: Low and stable inflation, steady growth, and fewer recessions (until 2008). Influences: * The adoption of inflation targeting as a monetary policy framework was primarily advocated by the New Keynesian school of economics, though it also drew support from monetarist and neoclassical synthesis ideas. A clear target (e.g., 2%) avoids the time-inconsistency problem (Kydland & Prescott, 1977). New Keynesians formalized inflation targeting with forward-looking models (e.g., Woodford’s Interest and Prices). Bernanke (later Fed Chair) co-authored influential papers supporting the framework. * "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon" → Central banks should focus on price stability. Friedman opposed pure discretion, favoring rules-based policy (e.g., constant money growth). * Combines Keynesian short-term stabilization with neoclassical long-term neutrality of money. Taylor Rule (1993) provided a formulaic approach to setting rates based on inflation/output gaps. |

| Global Financial Crisis (2008) | Global Financial Crisis (2008) & Unconventional Policy. Challenge: The 2008 crisis forced central banks to innovate as interest rates hit zero lower bound (ZLB). New Tools: Quantitative Easing (QE): Large-scale asset purchases (bonds, MBS) to inject liquidity. Forward Guidance: Communicating future policy intentions to shape expectations Negative Interest Rates (e.g., ECB, Bank of Japan). Expanded Mandates: Central banks (like the Fed) took on roles in financial stability and unemployment (e.g., dual mandate reinforced). After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), policymakers relied on a mix of economic ideas, but the dominant framework was an evolved form of New Keynesian economics, supplemented by insights from Post-Keynesianism, Monetarism (liquidity-focused), and Behavioral Economics. |

| Post-Crisis Era (2010s) | Post-Crisis Era (2010s). Normalization Attempts: The Fed and others tried to raise rates and shrink balance sheets (2015–2018), but markets became addicted to cheap money. New Challenges: Low neutral interest rates (r-star declined due to secular stagnation). Rising debt levels made economies more sensitive to rate hikes. |

| Modern Monetary Policy (2020–Present) | COVID-19 & Modern Monetary Policy (2020–Present) Pandemic Response: Ultra-low rates + massive QE (Fed’s balance sheet ballooned to ~$9 trillion). Fiscal-monetary coordination (e.g., direct stimulus payments). Inflation Surge (2021–2023): Post-COVID demand + supply shocks led to high inflation. Aggressive tightening (Fed hiked rates from 0% to 5.25–5.5% in 2022–2023). New Debates: "Higher for longer" rates vs. pre-2020 low-rate regime. Balance sheet reduction (quantitative tightening). Digital currencies (CBDCs) and fintech disruptions. |

6.5.2.2 Central Bank Targets

Price Inflation

Monetarism – "Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

Milton Friedman (1912–2006)

Permanent Income Hypothesis (consumption smoothing).

Argued for steady money growth (k-percent rule).

Employment

6.5.2.3 Monetary Policy Instruments

Inflation Targeting vs. Price Level Targeting

Nominal GDP Targeting

Rules vs. Discretion in Monetary Policy (Taylor Rule, Friedman’s k-percent rule)

Post-Keynesian Monetary Theory (Endogenous Money)

MMT

6.5.2.3.1 Fiscal Coordination

6.5.2.3.2 Interest Rates

Henry Thornton (1760–1815). Early analysis of central banking in "Paper Credit of Great Britain." Distinguished between nominal and real interest rates.

Irving Fisher (1867–1947) Fisher Equation (MV = PT) – formalized QTM. Distinguished between real and nominal interest rates (Fisher Effect).

Knut Wicksell (1851–1926). Natural Rate of Interest theory.

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) Liquidity Preference Theory (money demand for transactions, precaution, speculation).

Michael Woodford (b. 1955) New Keynesian Economics – interest rate rules (Taylor Rule extensions).

The Taylor rule, proposed by economist John B. Taylor, is a monetary policy guideline that suggests how central banks should adjust interest rates in response to changes in inflation and economic output.

Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP)

6.5.2.3.3 QE

6.5.2.3.4 Loans

6.5.2.3.5 Forward Guidance

Michael Woodford (b. 1955). New Keynesian Economics – interest rate rules (Taylor Rule extensions). Emphasized forward guidance.

6.5.2.3.6 Channels of Monetary Policy Transmission

Ben Bernanke (b. 1953). Credit Channel of Monetary Transmission (how banks affect the economy). Applied theory during the 2008 crisis as Fed Chair.

https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/the-transmission-of-monetary-policy.html

Knut Wicksell (1851–1926). Linked money supply, interest rates, and inflation (cumulative process).

6.6 The Planned Real Economy

6.6.1 Investment Demand

6.6.2 Allocation of Resources

Against Central Planning Mises' calculation problem: Without market prices, rational allocation is impossible Socialist systems lack the knowledge and incentives for proper allocation

Against Neoclassical Equilibrium Models Rejects the notion of "given" resources waiting to be allocated Critiques the perfect information assumptions of Walrasian models

Against Keynesian Aggregate Management Macro-level interventions distort the micro-level price signals needed for proper allocation "Stimulus" spending misdirects resources based on political rather than economic factors

-

Collectivized Risk of Credit

-

Winners and Loosers on Monetary Expansion

-

First can Invest with old prices

Entry Barriers

6.6.3 Cantillon Effects

6.7 Money Supply Growth

6.7.1 Supply and Demand Mismatches

6.7.1.1 Price Deflation

6.7.1.2 Price Inflation

6.7.1.3 Stagflation

6.7.1.4 Hyperinflation

6.7.2 Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT)

Post-Keynesian Monetary Theory (Endogenous Money)

Austrian School’s View on Money & Credit Cycles

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)

Hayek puts the Capital theory, the monetary theory and the price theory together to formulate the Austrian Theory of Trade Cycle

Hyman Minsky (1919–1996)

Financial Instability Hypothesis – boom-bust cycles due to credit.

"Stability is destabilizing."

Bubble after bubble

6.7.3 Currency Debasement

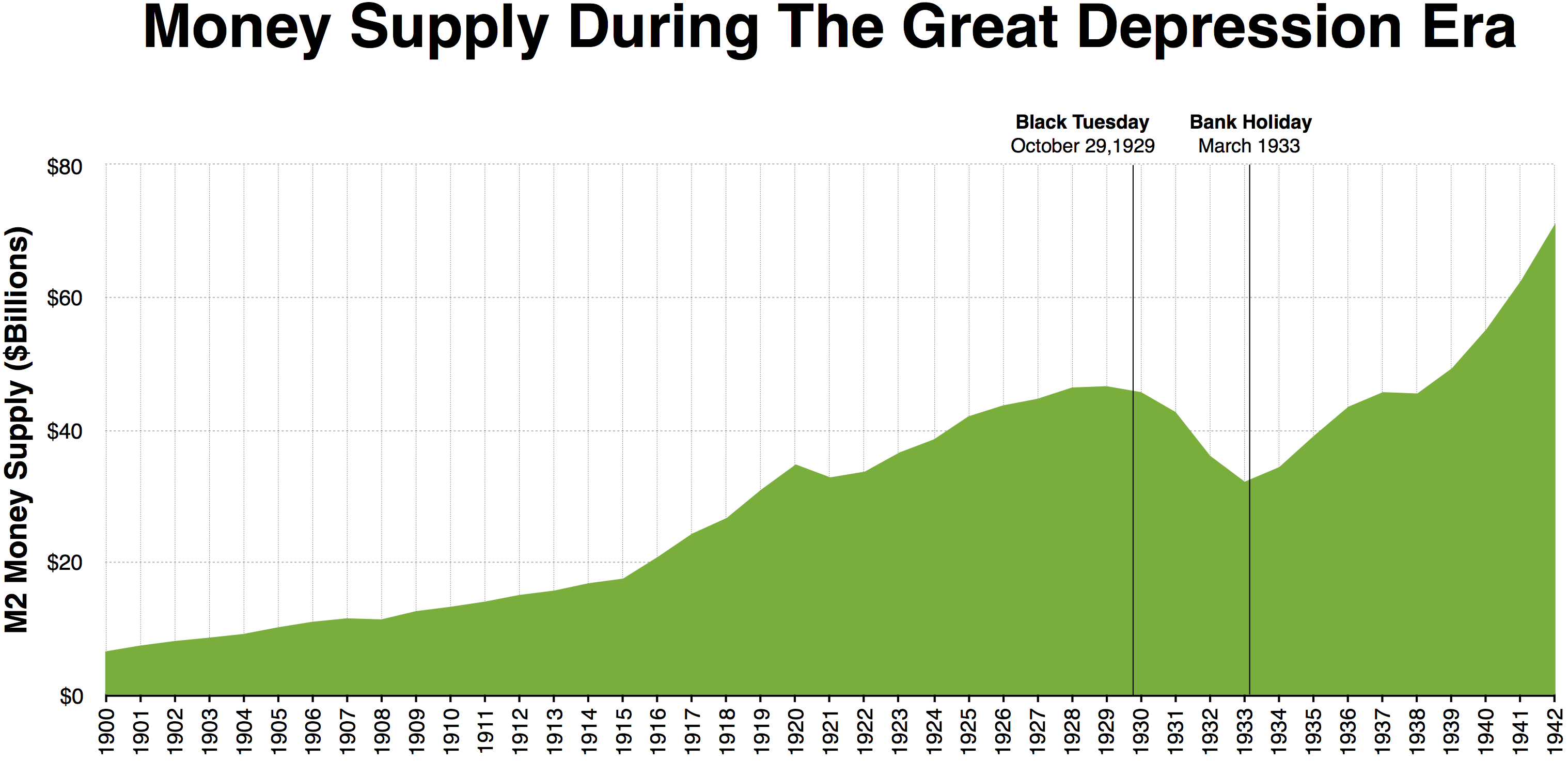

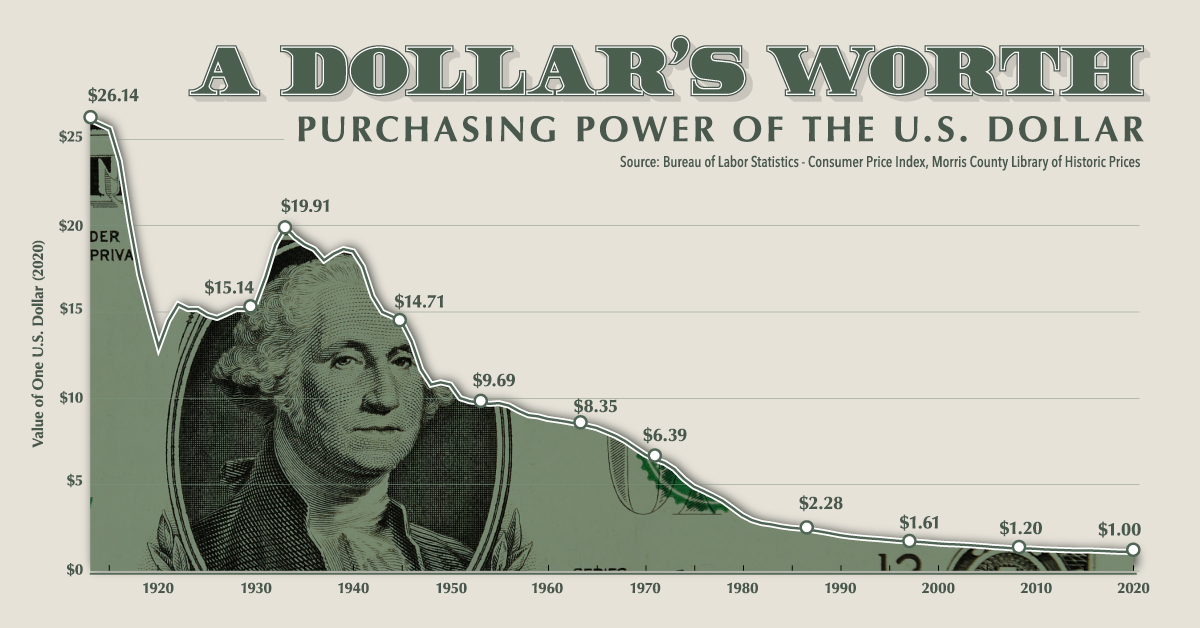

debasement occurs when M2 grows faster than GDP https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/debasement-what-it-and-isnt

purchasing power

race to the bottom

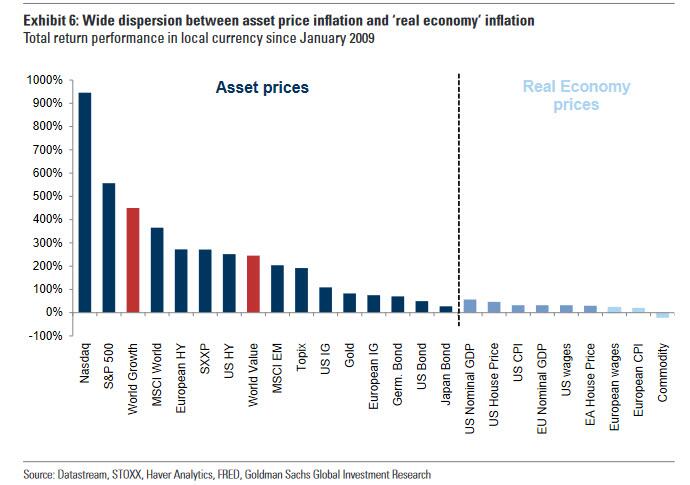

6.7.4 The Split Economy

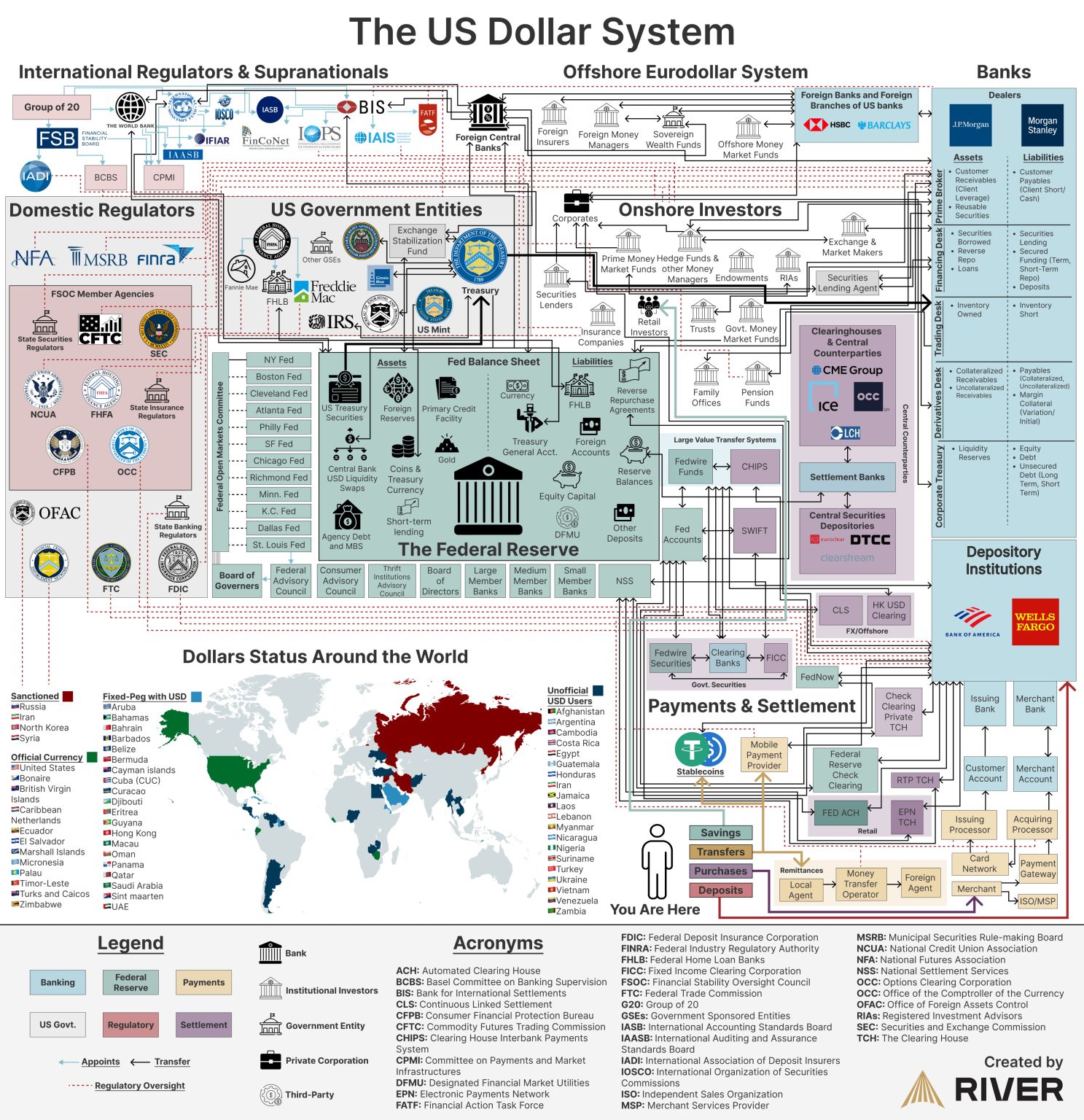

Since the money is not bound to real world value, from 1971, the economy has split in 2:

-

The real economy concerns the production, purchase and flow of goods and services (like oil, bread and labour) within an economy. Economic activity is conceptualized as ‗real‘ because real resources are applied to produce something which people can buy and use. Real economy can be measured by the GDP.

-

The financial system is mainly concerned either with moving funds around so that those who wish to buy can do so, or helping people to exchange ownership of the productive resources. Financial system is depegged from real consumer necessities.

price distortion

6.7.5 The Squeezed Real Economy

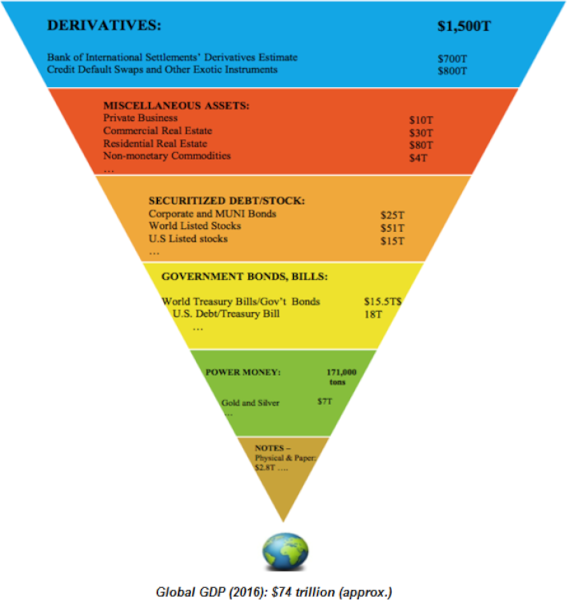

The monetary base for real economy is squeezed by the financial economy, and shrinking everyday. This blocks any progress for real economy, put barriers to entry to entrepreneurs creating increasingly Cantillon Effects and excluding citizens from the financial system. The trigger of this trend happened on 1971.

The Exter’s Pyramid of Liquidity illustrates the liquidity of assets arranged from the hardest to liquidate (complex derivatives and real estate) to the most liquid asset, physical gold. We can see how the world GDP (real economy) was a 5% of existing liquidity, including derivatives in 2016.

6.7.6 Reset

War as Reset

Jubileo as Reset

Hyperinflation as reset

No Reset, vicious circle where the money spins around issuers